Toronto City Hall

by Ninjalicious

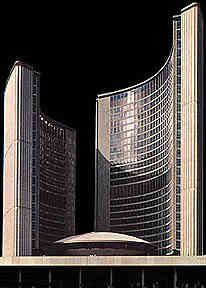

In 1957, the City of Toronto held the largest architectural competition ever, and invited 520 architects from around the world to submit their plans for Toronto's new City Hall. After a year of submissions and public debate, the avant-garde design proposed by Finnish architect Viljo Revell triumphed. The building was finally completed in 1965. Despite general enthusiasm, Revell's twin-towered structure has been controversial from the beginning: a contemporary letter to the editor dismissed the building as "two boomerangs over half a grapefruit." Frank Lloyd Wright described the building as "a headmarker for a grave," and added "future generations will look at it and say: 'This marks the spot where Toronto fell.'"

Toronto has certainly not fallen. In his book Accidental City, author Robert Fulford says "In Toronto, city-building has become an art of public revelation rather than private expression... The significant moment of change can be precisely dated: Monday, September 13, 1965, opening day at the New City Hall and Nathan Phillips Square. Modern architecture suddenly became legitimate and respectable." In the words of architectural historian William Kilbourn, new City Hall is "an enduring civic symbol that is one of the world's great buildings."

I think Toronto's City Hall is not only one of the most incredible buildings I have ever visited, but probably the single most significant building in Toronto's architectural history. While Toronto has long had more than its fair share of beautiful architecture, City Hall was Toronto's first significant building that wasn't a rectangle. Its success and popularity launched an era of architectural experimentation that lasted until the early 1990s, and gave Toronto one of the world's most distinctive and attractive cityscapes.

From the grand rotunda on the lower levels, to the white spaceship suspended in mid-air at the building's centre, to two crescent-shaped towers of unequal height, there are so many things to love about this bizarre building. I had to examine them all up close, from the bottom to the top.

Subbasement

My friend Sean and I entered City Hall's wondrous subbasement by pushing forcefully on a door at the bottom of the north stairwell. Once inside we began exploring very tentatively. As can be seen on City Hall blueprints, the building's subbasement is mostly one gigantic room, so we were constantly worried that an employee somewhere else on the level would spot our mischievous feet beneath all the pipes and vents.

City Hall has its own set of steam tunnels.

After an initial survey of the area, Sean and I climbed up a small ladder and entered what appeared to be a small vent-filled crawlspace. We soon realized the crawlspace was actually quite large and complex. We found a fairly shaky wooden ladder propped against pipes and walls which led up at least two storeys into a promising-looking shaft, but unfortunately our nerves weren't up for that dangerous and possibly noisy climb. Behind a small metal door nearby, Sean discovered a series of dark concrete tunnels filled with vents and water pipes, quite similar to college steam tunnels except without all the heat. We traversed the tunnels for a while before eventually concluding that every route led either to a dead end or back to the main portion of the subbasement.

City Hall's gigantic subbasement can be traversed on the floor or through the ducts.

Emerging back into the main subbasement, we continued our quest. Among our many finds were several blue wooden chests, which unfortunately were filled with old junk rather than treasure, a large stockpile of hazardous chemicals in barrels, some gigantic vents I climbed up inside, and a glorious industrial area we dubbed Valveland.

We had explored less than a tenth of the subbasement and were still having a great time when suddenly we heard a clunk. Sometimes clunks are nice, don't get me wrong, but this was not a nice clunk, rather more of a nearby-employee clunk. This particular clunk upset us both very greatly, and caused us to scurry in search of an exit quickly, while peeking under all the pipes and vents for feet and expecting to see a troop of black leather boots goose-stepping towards us at any moment. Sean found an elevator and was just about to summon it to our rescue when I stopped him; elevators have a nasty habit of dinging when they arrive, and service elevators sometimes have eyes. We instead scrambled and climbed back to the way we had come in and ran off up the stairs to the next level up. I later discovered that this elevator was not a service elevator at all, but simply the easternmost of the 11 public elevators which service the building (and the only elevator with an "SB" button). It requires no passcard, but it does ding.

We had explored less than a tenth of the subbasement and were still having a great time when suddenly we heard a clunk. Sometimes clunks are nice, don't get me wrong, but this was not a nice clunk, rather more of a nearby-employee clunk. This particular clunk upset us both very greatly, and caused us to scurry in search of an exit quickly, while peeking under all the pipes and vents for feet and expecting to see a troop of black leather boots goose-stepping towards us at any moment. Sean found an elevator and was just about to summon it to our rescue when I stopped him; elevators have a nasty habit of dinging when they arrive, and service elevators sometimes have eyes. We instead scrambled and climbed back to the way we had come in and ran off up the stairs to the next level up. I later discovered that this elevator was not a service elevator at all, but simply the easternmost of the 11 public elevators which service the building (and the only elevator with an "SB" button). It requires no passcard, but it does ding.

Basement

When Sean and I emerged from the stairwell and out into the loading bay in the basement, it was fairly clear we were somewhere we weren't supposed to be. We were in a large room with unfinished concrete walls and a concrete floor, filled with many boxes, crates and bins. A young employee across the room hadn't noticed us yet, but I elected to speak to him before he spoke to us. Upon receiving his gracious directions to the parking garage, Sean and I elected to call it an evening.

There are less suspicious and nerve-wracking ways to enter and explore City Hall's basement, as I later discovered. Several sections of the basement are open to the public, and it isn't always clearly marked where the public areas start and where they end. One such grey area lies in the vicinity of the City Archives and the Central Records Office. Though these two offices are essentially two branches of the same department, they are separated by a stroll through the parking garage under City Hall — one of the largest underground parking garages in the world. The employees sometimes complain about this, but as I see it chaotic layout is a small price to pay for getting to work inside a piece of sculpture.

City Archives and the Central Records Office are open to the public. Continuing down the hallway from Central Records, one can enter the off-limits, employee-only area of the basement without passing any signs. It's a nice basement. The floors, walls and ceilings are all concrete, painted stark white, muted aqua or bright red. There are pipes and vents galore, many unlocked doors to offices and maintenance rooms, as well as the aforementioned loading bay. Eventually the main hallway leads out through a set of glass doors marked "No Admittance Except On Business," and out into the employee cafeteria section of the basement. (A trick I used was to carry a piece of paper with the address for Central Records in my hand. If any employees had caught me and questioned me, I'm sure they would've had no trouble believing I was lost.)

The employee cafeteria doesn't have much to offer. Just outside the cafeteria, though, one finds an unmarked set of double doors with brown paper covering their small windows. When people cover their windows with brown paper, you know they're hiding something good. Immediately beyond the doors one finds a small lobby filled with all sorts of odd junk; a door leading to a large mailroom filled with stationery, City Hall merchandise and election leftovers; and grated doors leading to an old freight elevator which is marked "Not For Public Use".

The employee cafeteria doesn't have much to offer. Just outside the cafeteria, though, one finds an unmarked set of double doors with brown paper covering their small windows. When people cover their windows with brown paper, you know they're hiding something good. Immediately beyond the doors one finds a small lobby filled with all sorts of odd junk; a door leading to a large mailroom filled with stationery, City Hall merchandise and election leftovers; and grated doors leading to an old freight elevator which is marked "Not For Public Use".

My friend Steve and I are fairly private people, so when we first stumbled upon the freight elevator we felt no qualms about pulling back the grated door and hopping aboard. The elevator was dirty and looked like it hadn't been used in some time. The light had burned out, so we were riding in darkness. I used a flashlight to locate the buttons, and hit the up button. The old elevator grudgingly roared to life and began a very slow climb, eventually dropping us off one level above. We got out and explored what seemed to be an unlit storage room which was in the midst of being converted into some sort of office. We examined some large blueprints by flashlight, but remained unenlightened. We found a wide variety of junk but didn't notice an exit, so we returned to the elevator and began our return to the basement. As we descended, however, we heard voices. I exchanged a panicked look with Steve and then quickly hit the emergency stop button and turned off my flashlight. As the elevator jerked to a halt between the two floors, we stood still in the total darkness and confirmed that there were indeed men's voices coming from below. After uttering a quick prayer that the elevator would allow us to change direction in mid-descent, I hit the up button and we returned to the second floor. We then propped the elevator door open so the men working below couldn't take the elevator up to investigate, and our desperation inspired us to find an exit rather quickly. We emerged into the hallway outside the library on the first floor. Since our exploration, a small portion of this area has been opened as the Building Manager's Office.

My friend Steve and I are fairly private people, so when we first stumbled upon the freight elevator we felt no qualms about pulling back the grated door and hopping aboard. The elevator was dirty and looked like it hadn't been used in some time. The light had burned out, so we were riding in darkness. I used a flashlight to locate the buttons, and hit the up button. The old elevator grudgingly roared to life and began a very slow climb, eventually dropping us off one level above. We got out and explored what seemed to be an unlit storage room which was in the midst of being converted into some sort of office. We examined some large blueprints by flashlight, but remained unenlightened. We found a wide variety of junk but didn't notice an exit, so we returned to the elevator and began our return to the basement. As we descended, however, we heard voices. I exchanged a panicked look with Steve and then quickly hit the emergency stop button and turned off my flashlight. As the elevator jerked to a halt between the two floors, we stood still in the total darkness and confirmed that there were indeed men's voices coming from below. After uttering a quick prayer that the elevator would allow us to change direction in mid-descent, I hit the up button and we returned to the second floor. We then propped the elevator door open so the men working below couldn't take the elevator up to investigate, and our desperation inspired us to find an exit rather quickly. We emerged into the hallway outside the library on the first floor. Since our exploration, a small portion of this area has been opened as the Building Manager's Office.

One and Two

The first and second floors are more or less open to the public on business during regular working hours. After 5p.m., City Hall security draws blue ropes across the main entrance to this section of the building and compels visitors to sign in at the security desk. This unpleasantness can be avoided by heading down to the area near the parking garage (which, as part of Toronto's underground walkway the PATH, is open very late), and taking the elevator up from there. Early evening is the optimal time to explore the semi-public areas of the building, as this is late enough for most employees to have gone home for the night, but early enough that one won't seem out of place walking around.

The first floor features the library and bookstore (good places to ask about the building's history), the information desk (a good place to ask where to find something in the building), the security desk (a bad place to ask about anything), Permit Alley and a bunch of generic offices.

The second floor features more offices and conference rooms, which are surprisingly accessible and abandoned in the evening. Almost all the outside walls are floor-to-ceiling glass panels, which offer a good view of which offices are empty. Very few doors are locked. I was able to stroll through a glass door into the mayor's public office (avoiding the gaze of a ceiling-mounted security camera without difficulty) and examine various cupboards, desks and coatrooms unimpeded. I even discovered what seemed to be the mayor's private washroom — he uses Colgate.

The second floor features more offices and conference rooms, which are surprisingly accessible and abandoned in the evening. Almost all the outside walls are floor-to-ceiling glass panels, which offer a good view of which offices are empty. Very few doors are locked. I was able to stroll through a glass door into the mayor's public office (avoiding the gaze of a ceiling-mounted security camera without difficulty) and examine various cupboards, desks and coatrooms unimpeded. I even discovered what seemed to be the mayor's private washroom — he uses Colgate.

While I was exploring the second floor one afternoon, I noticed a group of a dozen or so university students walking down one of the hallways and decided to tail them from a distance and see what they were up to. It became apparent that they were architecture students in the middle of a tour of the building. I toyed with the notion of joining the group. What I was wearing would probably allow me to pass for a student, but there were only a dozen of them, so I knew I'd be conspicuous... As I was weighing the pros and cons, however, the tour guide began fumbling with keys to take the students into some locked boardrooms. The chance to peek behind locked doors was irresistible, so I hauled out a notebook and joined the group.

As he led us around to various non-public boardrooms, libraries and offices, our tour guide shot me several suspicious looks, as if he wasn't sure he recognized me. When he looked my way, I would just make some comment about the building to one of my fellow students, who seemed too timid to confront me and mention they had never seen me in their class before. Eventually our guide (whose business card introduced him as Richard Winter, Facility Planner) must have just assumed I was a latecomer, for he soon relaxed and began to share his knowledge of the building with me. As Mr. Winter led us through the councilors' offices and staff rooms, he would occasionally pause to ask for questions from the group. My adopted classmates were a rather incurious group, so I asked the questions. Mr. Winter seemed very impressed with my knowledge of the building's history and architecture, and was pleased to answer my questions about the basement levels and the closed Observation Deck (which, sadly, he did not have keys for).

As he led us around to various non-public boardrooms, libraries and offices, our tour guide shot me several suspicious looks, as if he wasn't sure he recognized me. When he looked my way, I would just make some comment about the building to one of my fellow students, who seemed too timid to confront me and mention they had never seen me in their class before. Eventually our guide (whose business card introduced him as Richard Winter, Facility Planner) must have just assumed I was a latecomer, for he soon relaxed and began to share his knowledge of the building with me. As Mr. Winter led us through the councilors' offices and staff rooms, he would occasionally pause to ask for questions from the group. My adopted classmates were a rather incurious group, so I asked the questions. Mr. Winter seemed very impressed with my knowledge of the building's history and architecture, and was pleased to answer my questions about the basement levels and the closed Observation Deck (which, sadly, he did not have keys for).

In fact, by the time we had toured the rest of the lower levels and taken the elevator up to tour the facility planning offices on the East Tower's ninth level, it was fairly clear that I had gone from being a non-student to being the teacher's pet. One of my jealous peers finally mustered up the courage to ask me if I was a student, to which I replied that no, I was a reporter writing an article about the changes to City Hall and that I had obtained his professor's permission to come along on the tour, which was enough to ease his worried mind. The facility planning people offered us a wide variety of blueprints of the building, and were pleased to speak at length about the architectural history of the building and what they hoped for its future. Mostly, they seemed quite attached to the odd building, and forgiving of its faults.

The Spaceship

The Spaceship

City Hall's Council Chambers are perhaps the most bizarre feature of a decidedly bizarre building. The 4,000-tonne, poured-concrete ellipsoid pod is held three storeys in the air by a single, six-meter thick concrete column in its centre. This mushroom-shaped column plunges 16 meters below floor level into solid bedrock. The pod is generally referred to as "the spaceship" in articles on the building's architecture.

The spaceship is open to the public only during meetings of city council; at all other times, the elevators refuse to take "C" for an answer. After many failed attempts to visit during a city council meeting, I finally managed to take the elevator up to the C level.

When I emerged into the C level lobby, I heard councilors arguing in the main chamber, but no one was in my immediate vicinity so I explored some stationery-filled closets and some unusual climbing spaces. I got my businessman disguise a little dusty in the process, so I decided to wash up a little before making my way out to the spectator gallery of the Council Chambers. As I was washing my hands, some odd intuition, or perhaps just my habit of trying to open everything, led me to pull on the metal cover of the towel dispenser in the men's washroom. I was rather surprised when the cover turned out to be an unlocked door leading into a darkened janitor's closet. I slipped through, closed the towel dispenser behind me, and had a peek. In addition to the entrance I had used, there were two other doors: one leading to a storeroom filled with nameplates and telephones, and one marked "Please Do Not Lock This Door." (Mental note: Bring lots of "Please Do Not Lock This Door" signs along on future explorations.)

Luckily, some employee was obedient. I opened the unlocked door and began groping the dark wall beyond for a light switch. When I hit the lights, I couldn't help but utter an involuntary ohmigod. I was inside the rim of the spaceship! The area was a dirty concrete crawlspace which circled the council chamber. I was better dressed for exploring offices than tunnels, but I couldn't resist crawling around the extremely dusty, sloping walls of the spaceship. I found little more than some machinery, some janitorial supplies and some leftover posters and junk. I concluded that this area was not built purposefully, but was simply a leftover area deemed too cramped to be useful.

Luckily, some employee was obedient. I opened the unlocked door and began groping the dark wall beyond for a light switch. When I hit the lights, I couldn't help but utter an involuntary ohmigod. I was inside the rim of the spaceship! The area was a dirty concrete crawlspace which circled the council chamber. I was better dressed for exploring offices than tunnels, but I couldn't resist crawling around the extremely dusty, sloping walls of the spaceship. I found little more than some machinery, some janitorial supplies and some leftover posters and junk. I concluded that this area was not built purposefully, but was simply a leftover area deemed too cramped to be useful.

I imagine I spent 20 minutes exploring in all. I then exited the crawlspace, returned to the janitor's room, exited through the towel dispenser into the men's washroom, and returned to the lobby of the Council Chambers. It was now empty and silent. Hesitantly, I opened the door out to the Council Chamber floor, where I found the area abandoned. I had the spaceship to myself! I examined the council area, the press gallery, the AV equipment, and the notes some of the councilors had left behind ... but all too soon, a janitor showed up and implied with an abundance of dirty looks that I had better be on my way. I took his picture and left.

When I returned to the Council Chambers a week later to capture my findings on video, I had a rather terrifying experience. Once again, I had accessed the Council Chamber pod after a meeting and had the entire spaceship to myself. I had returned to the Land Beyond the Towel Dispenser, and was exploring and filming in the storage areas, when suddenly the entire pod filled with a horrendous wailing. I was sure the piercingly loud siren noise was directed at me, and imagined I must've been caught by a security camera or motion detector. I put away my camcorder and exited the washroom. I strolled to the elevator and hit the down button with my shaking hand, but the down arrow failed to light up. I then noticed that the elevator was on emergency recall. And I realized I was on the only level of City Hall not publicly accessible by stairs (aside from emergency exit stairs).

When I returned to the Council Chambers a week later to capture my findings on video, I had a rather terrifying experience. Once again, I had accessed the Council Chamber pod after a meeting and had the entire spaceship to myself. I had returned to the Land Beyond the Towel Dispenser, and was exploring and filming in the storage areas, when suddenly the entire pod filled with a horrendous wailing. I was sure the piercingly loud siren noise was directed at me, and imagined I must've been caught by a security camera or motion detector. I put away my camcorder and exited the washroom. I strolled to the elevator and hit the down button with my shaking hand, but the down arrow failed to light up. I then noticed that the elevator was on emergency recall. And I realized I was on the only level of City Hall not publicly accessible by stairs (aside from emergency exit stairs).

For about five minutes I stood waiting in front of the elevator, filled with panic but preparing to look nonchalant when security arrived, when suddenly a voice came over the public address system saying "Attention attention, an alarm has been sounded in the basement of the East Tower, please stand by." The announcement was followed by more piercing wails for a few moments, and then another announcement saying that there had been a fire in the East Tower basement. After another five minutes of standing alone in the pod listening to the shrieking alarm, there came another announcement, which informed me that the fire had been dealt with and all employees could return to their stations. The elevators came back to life and I was once again a free man. I later asked at the information desk about the sirens and learned that all the elevators in the building had been automatically shut off, and that the siren had sounded throughout the building. The moral: don't accidentally trigger any alarms in City Hall.

The Two Towers

City Hall's most prominent features are its two large, curved office towers of unequal height. Floors 3-19 of the West Tower and Floors 3-25 of the East Tower are given over to the offices of city employees, aside from the mechanical rooms located on the 11th storey of the West Tower and the 13th storey of the East. The office floors have a rather unusual layout: because of the curvature of the towers, the floors are crescent shaped, and one cannot see one end of the floor from the other. On each floor, there are doors at the north and sound ends of the floor leading to publicly accessible stairwells. The elevators are in the middle of each floor. The proper offices line the back wall near the elevator bank; most employees work in small cubicles near the windows.

For those who enjoy exploring offices, the office levels are truly a goldmine, whether accessed via elevators or the public stairwells. Almost all the reception areas are now left unstaffed (for financial reasons), so there is no one around to turn visitors away. The employees have the apathetic "not-my-department" attitude you might expect of civil servants, so if you can act like you're supposed to be there, you won't be harassed. No office employees have ever questioned me, even while I've been walking around their offices taking pictures. If you prefer not to deal with the human element, visit during the evening. The office levels remain open after working hours. From roughly 6 p.m. onward, the explorer's only concern is the handful of security guards and janitors who patrol the building. For those who aren't interested in offices, however, there isn't really much point to the middle levels of the office towers, other than to separate the interesting lower levels from the interesting upper levels.

Attics and Roofs

Once upon a time, City Hall was one of the tallest buildings in Toronto, and the Observation Deck on the East Tower's 27th floor was a popular attraction. When skyscrapers were erected across from City Hall in the 1970s, however, the Observation Deck lost its appeal. It was permanently closed to the public more than a decade ago, and now the elevators only travel as high as the offices on the 25th floor. The public elevators, that is.

Disembarking at the 25th floor, one emerges into one of the ordinary abandoned reception areas. When I visited in the early evening, the whole floor was empty and open to my use, so I set about finding a way up. Behind a glass door I caught a glimpse of some stairs heading up, but this door was marked "Do Not Enter: Observation Deck Permanently Closed" and some boxes and things had been piled around it. At the north end of the tower I found an easier way up: an employee elevator that travels only between the 25th, 26th, and 27th floors.

Disembarking at the 25th floor, one emerges into one of the ordinary abandoned reception areas. When I visited in the early evening, the whole floor was empty and open to my use, so I set about finding a way up. Behind a glass door I caught a glimpse of some stairs heading up, but this door was marked "Do Not Enter: Observation Deck Permanently Closed" and some boxes and things had been piled around it. At the north end of the tower I found an easier way up: an employee elevator that travels only between the 25th, 26th, and 27th floors.

Working my way up, I first visited the 26th floor, which turned out to be a level of mechanical rooms, ventilation shafts and the like. I climbed up a ladder into a fan room but found no entrance to the outdoors. I took some stairs in the maintenance area up to the 27th floor, where I was disappointed but not surprised to see that all doors leading outside to the Observation Deck were tightly padlocked shut. There was little I could do but stare through the windows longingly, and snoop about briefly in the elevator control room of the East Tower. I tried approaching the Observation Deck from other stairwells and from the elevator, but all routes were dead ends. While the 27th floor is still accessible, the Observation Deck and the East Tower roof are definitely off limits.

Working my way up, I first visited the 26th floor, which turned out to be a level of mechanical rooms, ventilation shafts and the like. I climbed up a ladder into a fan room but found no entrance to the outdoors. I took some stairs in the maintenance area up to the 27th floor, where I was disappointed but not surprised to see that all doors leading outside to the Observation Deck were tightly padlocked shut. There was little I could do but stare through the windows longingly, and snoop about briefly in the elevator control room of the East Tower. I tried approaching the Observation Deck from other stairwells and from the elevator, but all routes were dead ends. While the 27th floor is still accessible, the Observation Deck and the East Tower roof are definitely off limits.

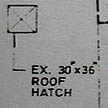

Having failed in the east, I decided to seek my fortune in the west. Though the West Tower is a few storeys shorter than the East Tower, it is just as spunky. The West Tower's elevator stops at the 19th floor. The 19th floor, like most floors in City Hall, has no receptionist and no security, so it is wide open to exploration. A non-public staircase is located immediately north of the elevator bank, through an unmarked, unlocked beige door. This dirty, disused and dimly-lit staircase only goes between the 19th and 20th storeys. At the top of the stairs are two doors, one large and one small. The large door leads to a locker room and a chemical room. The small door features a homemade sign reading "Please Keep These Doors Closed and Locked!" Luckily, some employee was disobedient.

Travelling through the small door, one emerges into a very tall, very wide concrete chamber, reminiscent of the water filtration plant the aliens took over in the movie V. The huge crescent-shaped chamber is dominated by four mammoth watertanks. Pipes are everywhere. The room is filled with puddles and the delicious sounds of dripping and bubbling water. The lights were off, but the ceiling and parts of the walls are metal mesh and some outside light pours through. So does the cold rain from the outside, which pelts down on the hot pipes with little hisses of steam.

As mentioned, the 20th storey's most notable features are two pairs of massive, 30-foot-tall watertanks, which are separated from one another by mazes of hot and cold metal pipes at various heights. One must climb over, under, around and through the pipes (carefully avoiding the scalding hot ones) simply in order to move around the floor. There are no ladders or stairs leading to the top of the watertanks, but there are many useful pipes, railings and ledges that can be used to scale one's way to the top.

Several huge watertanks fill the area at the top of the west tower.

Being careful not to look down, I climbed atop the railings of a metal staircase and managed to hoist myself atop watertank three. From the top of the tank, I peered down at the huge whirring fan blades inside the tank, and stopped to take some pictures of the churning, bubbling water. I then walked along the metal catwalks between the various watertanks and gave each a thorough examination. Everything seemed in order.

Climbing back down from atop the watertanks, I took the stairs up half a level, and tentatively opened a door. The coast was clear, so I began examining the layout and machinery of what I soon determined to be the West Tower's very noisy elevator control room. I looked through some logbooks and technical diagrams, and watched the metal cables snap taught and whiz about furiously each time an elevator was summoned to a new floor.

After discovering a grate in the floor leading down to a darkened shaft under the elevator control room, I quickly pried this off and climbed down to take a look, but it seemed just a little too dangerous and dark to do much exploring down there by myself. Climbing back up, I replaced the grate and exited the elevator room.

After discovering a grate in the floor leading down to a darkened shaft under the elevator control room, I quickly pried this off and climbed down to take a look, but it seemed just a little too dangerous and dark to do much exploring down there by myself. Climbing back up, I replaced the grate and exited the elevator room.

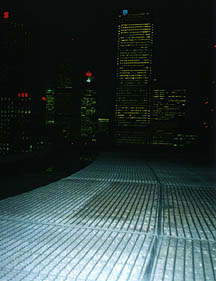

Back outside in the watertank chamber, rain was pouring through the grated ceiling and beginning to soak the room, so I figured it was time to check out the roof. I pulled down a rope (attached to a pulley, attached to the grate) to open the heavy metal grate to the roof and tied the rope in place. I then climbed up the wet metal ladder and emerged onto the metal mesh roof of the West Tower. There is no solid floor to the West Tower roof, so I was supported only by widely-spaced grating. The nearest concrete floor was two storeys down. There is no ledge around the edges of the roof to offer any concealment or protection from the gusting winds. Standing on the slippery metal mesh 21 storeys up felt very precarious, particularly since I was in clear view of all the offices on the upper levels of the East Tower. Still, the roof offers a great view, and it's a great feeling to stand on top of City Hall in the rain at night, the only solid floor 40 feet down, the air filled with steam rising off the pipes below. Moments like these fill me with love for all things industrial and off-limits, and convince me further that infiltrating is truly the good life.

Back outside in the watertank chamber, rain was pouring through the grated ceiling and beginning to soak the room, so I figured it was time to check out the roof. I pulled down a rope (attached to a pulley, attached to the grate) to open the heavy metal grate to the roof and tied the rope in place. I then climbed up the wet metal ladder and emerged onto the metal mesh roof of the West Tower. There is no solid floor to the West Tower roof, so I was supported only by widely-spaced grating. The nearest concrete floor was two storeys down. There is no ledge around the edges of the roof to offer any concealment or protection from the gusting winds. Standing on the slippery metal mesh 21 storeys up felt very precarious, particularly since I was in clear view of all the offices on the upper levels of the East Tower. Still, the roof offers a great view, and it's a great feeling to stand on top of City Hall in the rain at night, the only solid floor 40 feet down, the air filled with steam rising off the pipes below. Moments like these fill me with love for all things industrial and off-limits, and convince me further that infiltrating is truly the good life.

This article originally appeared in Infiltration 8, together with profiles of Metro Hall and Old City Hall, and an article on being chased to the new upper levels of the Royal York Hotel.

|